Frontier AI Auditing: Toward Rigorous Third-Party Assessment of Safety and Security Practices at Leading AI Companies

Miles Brundage¹*, Noemi Dreksler², Aidan Homewood², Sean McGregor¹, Patricia Paskov³, Conrad Stosz⁴, Girish Sastry⁵, A. Feder Cooper¹, George Balston¹, Steven Adler⁶, Stephen Casper⁷, Markus Anderljung², Grace Werner¹, Sören Mindermann⁵, Vasilios Mavroudis⁸, Ben Bucknall⁹, Charlotte Stix¹⁰, Jonas Freund², Lorenzo Pacchiardi¹¹, José Hernández-Orallo¹¹, Matteo Pistillo¹⁰, Michael Chen¹², Chris Painter¹², Dean W. Ball¹³, Cullen O’Keefe¹⁴, Gabriel Weil¹⁵, Ben Harack³, Graeme Finley⁵, Ryan Hassan¹⁶, Scott Emmons⁵, Charles Foster¹², Anka Reuel¹⁷, Bri Treece¹⁸, Yoshua Bengio¹⁹, Daniel Reti²⁰, Rishi Bommasani¹⁷, Cristian Trout²¹, Ali Shahin Shamsabadi²², Rajiv Dattani²¹, Adrian Weller¹¹, Robert Trager³, Jaime Sevilla²³, Lauren Wagner²⁴, Lisa Soder²⁵, Ketan Ramakrishnan²⁶, Henry Papadatos²⁷, Malcolm Murray²⁷, Ryan Tovcimak²⁸

¹AVERI ²GovAI ³Oxford Martin AI Governance Initiative ⁴Transluce ⁵Independent ⁶Clear-Eyed AI ⁷MIT CSAIL ⁸Alan Turing Institute ⁹University of Oxford ¹⁰Apollo Research ¹¹University of Cambridge ¹²METR ¹³Foundation for American Innovation ¹⁴Institute for Law and AI ¹⁵Touro University Law Center ¹⁶New Science ¹⁷Stanford University ¹⁸Fathom

¹⁹Mila, Université de Montréal ²⁰Exona Lab ²¹AI Underwriting Company ²²Brave Software ²³Epoch AI ²⁴Abundance Institute ²⁵interface ²⁶Yale University ²⁷SaferAI ²⁸UL Solutions

January 2026

Listed authors contributed significant writing, research, and/or review for one or more sections. The sections cover a wide range of empirical and normative topics, so with the exception of the corresponding author (Miles Brundage, miles.brundage@averi.org), inclusion as an author does not entail endorsement of all claims in the paper, nor does authorship imply an endorsement on the part of any individual’s organization.

Executive Summary

Key paper takeaways

Despite their rapidly growing importance, AI systems are subject to less rigorous third-party scrutiny than many of the other social and technological systems that we rely on daily such as consumer products, corporate financial statements, and food supply chains. This gap is becoming increasingly untenable as AI becomes more capable and widely deployed, and it inhibits confident deployment of AI in high-stakes contexts.

Transparency alone cannot enable well-calibrated trust in the most capable (“frontier”) AI systems and the companies that build them: many safety- and security-relevant details are legitimately confidential and require expert interpretation, and third parties are right to be skeptical of companies "checking their own homework" given the track record of that approach in other industries.

We outline a vision for frontier AI auditing, which we define as rigorous third-party verification of frontier AI developers’ safety and security claims, and evaluation of their systems and practices against relevant standards, based on deep, secure access to non-public information.

Frontier AI audits should not be limited to a company’s publicly deployed products, but should instead consider the full range of organization-level safety and security risks, including internal deployment of AI systems, information security practices, and safety decision-making processes.

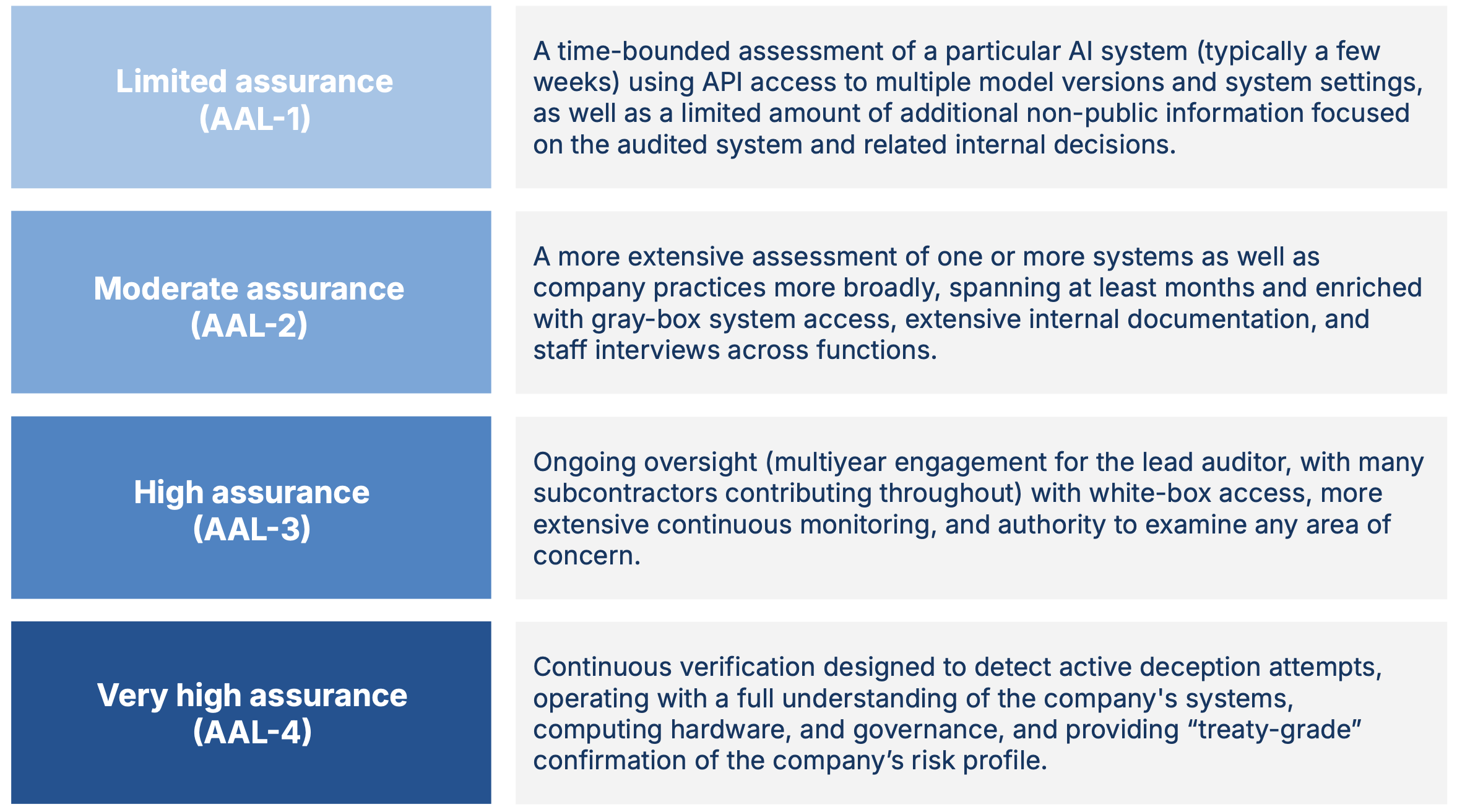

We describe four AI Assurance Levels (AALs), the higher levels of which provide greater confidence in audit findings. We recommend AAL-1 as a baseline for frontier AI generally, and AAL-2 as a near-term goal for the most advanced subset of frontier AI developers.

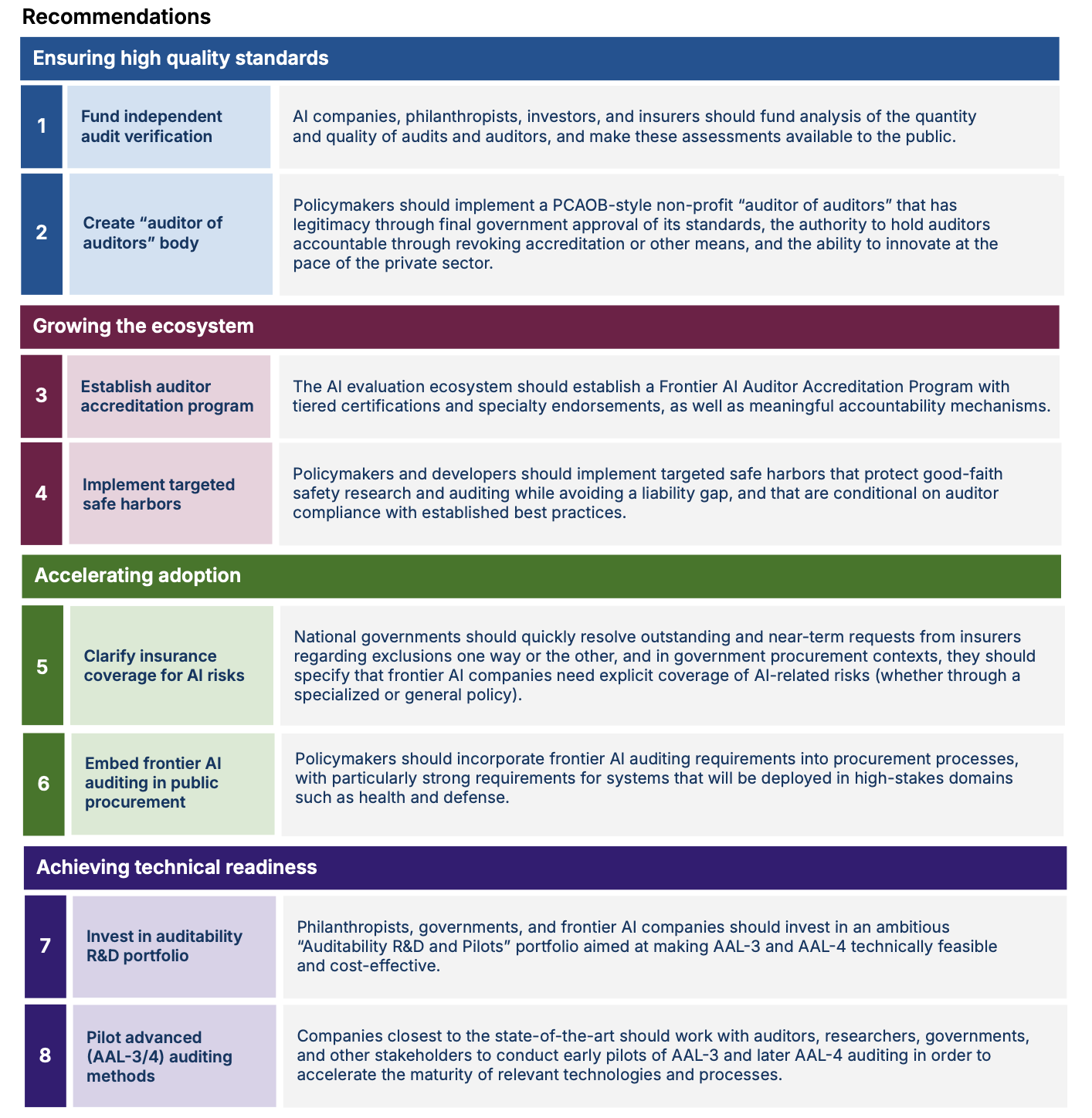

Achieving the vision we outline will require (1) ensuring high quality standards for frontier AI auditing, so it does not devolve into a checkbox exercise or lag behind changes in the industry; (2) growing the ecosystem of audit providers at a rapid pace without compromising quality; (3) accelerating adoption of frontier AI auditing by clarifying and strengthening incentives; and (4) achieving technical readiness for high AI Assurance Levels so they can be applied when needed.

Frontier AI auditing motivations

Artificial intelligence (AI) is rapidly becoming critical societal infrastructure. Every day, AI systems inform decisions that affect billions of people. Increasingly, they also make consequential decisions autonomously. Although these technologies hold incredible promise, the pace of development and deployment has outpaced the creation of institutions that ensure AI works safely and as advertised.

This institutional gap is especially important for the most capable (“frontier”) systems — general-purpose AI models and systems whose performance is no more than a year behind the state-of-the-art — which many experts expect to exceed human performance across most tasks within the coming years. Already, developers of frontier AI systems need to prevent harmful system failures (e.g., outputting false medical information or buggy code), weaponization by malicious parties (e.g., to carry out cyberattacks), and theft of or tampering with sensitive data. The magnitude of risks that need to be managed is growing rapidly.

AI users, policymakers, investors, and insurers need reliable ways to verify that promised technical safeguards exist and to detect when they do not. This is challenging because the technology is complex, fast-moving, and often proprietary. Public transparency alone cannot solve this problem since many key details are — and often should remain — confidential, and require expert judgment to interpret. Many industries outside of AI already address similar challenges through independent auditors who review sensitive, non-public information and publish trustworthy conclusions that outsiders can rely on. We argue that similar practices are needed in the AI industry: broad, sustainable adoption of AI over time requires a solid foundation of trust built on credible scrutiny by independent experts.

Toward this end, we propose institutions designed to give stakeholders — including those who are uncertain about or even strongly skeptical of frontier AI companies — justified confidence that this critical technology is being developed safely and securely. Specifically, we describe and advocate for frontier AI auditing: rigorous third-party verification of frontier AI developers’ safety and security claims, and evaluation of their systems and practices against relevant standards, based on deep, secure access to non-public information.

An ecosystem of private sector frontier AI auditors (both for-profit and non-profit) would enable widespread confidence that frontier AI systems can be adopted broadly and would avoid reliance on companies “grading their own homework,” an approach with a checkered track record in many industries. It would also avoid relying entirely on governments to have the technical expertise, capacity, and agility to ensure high standards for frontier AI safety and security. If well-executed and scaled, frontier AI auditing would improve safety and security outcomes for users of AI systems and other affected parties, create a system to learn and update standards based on real-world outcomes, and enable more confident investment in and deployment of frontier AI, especially in high-stakes sectors of the economy.

Summary of the proposal

Drawing on our analysis of current practices in AI and lessons from other industries with more mature assurance regimes, we recommend eight interlinked design principles for a long-term vision for frontier AI auditing. This vision is deliberately ambitious to match the rising stakes as frontier AI capabilities advance:

Scope of risks: Comprehensive coverage of four key risk categories. Frontier AI auditing should focus on four risk categories: risks from (1) intentional misuse of frontier AI systems (e.g., for cyberattacks); (2) unintended frontier AI system behavior (e.g., errors harming the user, their property, or third parties due to pursuing the wrong goal or having an unreliable performance profile); (3) information security (e.g., theft of an AI model or user data); and (4) emergent social phenomena (e.g., addiction to AI or facilitation of self-harm). For each category of risks, auditors should (a) verify company claims and (b) evaluate the company’s systems and practices against its stated safety and security policies, applicable regulations, and industry best practices.

Organizational perspective: Auditing companies’ safety and security practices as a whole, not just individual models and systems. Auditors should use an organization-level perspective to avoid abstraction errors (i.e., forming the wrong conclusion by treating a partial or simplified unit of analysis, such as evaluating a specific component in isolation, as if it were sufficient to assess overall system and organizational risk). Risk does not come from AI models alone; it emerges from the interaction of three overarching components: digital systems, computing hardware, and governance practices, and harm can arise even when a model is never deployed in external-facing systems. Rigorous, but isolated, model and system evaluations are therefore insufficient to evaluate all safety and security claims on their own. And while individual audits may focus on particular domains depending on their goals, the ecosystem as a whole should ensure comprehensive coverage across all three components in assessing safety and security claims.

Figure 1: Four AI Assurance Levels (AALs) for different frontier AI audits.

Levels of assurance: A framework for calibrating and communicating confidence in audit conclusions. Not all audits provide the same level of certainty, and stakeholders need to understand these differences. We propose AI Assurance Levels (AALs) as a means of clarifying what kind of assurance particular frontier AI audits provide (Figure 1). At lower levels, auditors and other stakeholders rely more heavily on information provided by the company and can primarily speak to a particular system’s properties. At higher levels, auditors take fewer assumptions for granted, and assess the full range of relevant company systems, organizational processes, and risks. At the highest level, auditors can rule out the possibility of materially significant deception by the auditee. Determining the appropriate AAL for different contexts and purposes is complex, but we recommend AAL-1 (the peak of current practices in AI) as a starting point for frontier AI generally, and AAL-2 as a near-term goal for the companies closest to the state-of-the-art. AAL-2 involves greater access to non-public information, less reliance on companies’ statements, and a more holistic assessment of company-level risks. The two highest assurance levels (AAL-3 and AAL-4) are not yet technically and organizationally feasible, but we outline research directions to change this.

Access: Deep enough to assure auditors and other stakeholders, secure enough to reassure auditees. Frontier AI auditors should receive deep, secure access to non-public information of various kinds — including model internals, training processes, compute allocation, governance records, and staff interviews — proportional to the audit’s scope and the level of assurance being sought for the audit. Access arrangements should protect intellectual property and security-sensitive information using mechanisms imported from other domains (e.g., sharing certain information with a subset of the auditing team on-site under a restrictive nondisclosure agreement) and newly-developed techniques (e.g., AI-powered summarization or analyses of information that is too sensitive to be directly shared).

Continuous monitoring: Living assessments, not stale PDFs. AI systems change constantly, including through adjustments to the underlying model(s), surrounding software, and shifts in user behavior. An audit conclusion that was accurate at the time of the assessment may become misleading in some respects within days or weeks. Audit findings should therefore carry explicit assumptions and validity conditions, and should be automatically deprecated when key underlying assumptions no longer hold. A mature auditing ecosystem will combine periodic deep assessments of slower-moving elements (e.g., governance, safety culture) with event-triggered reviews of major changes (e.g., new releases, serious incidents) and continuous automated monitoring of fast-changing surfaces (e.g., API behavior, configuration drift), enabling timely detection of changes that could invalidate prior conclusions.

Independent experts: Trustworthy results through rigorous independence safeguards and deep expertise. Auditors must be genuinely independent third parties, free from commercial or political influence, and have deep expertise across AI evaluation, safety, security, and governance. Safeguarding independence requires mandatory disclosure of financial relationships, standardized terms of engagement that prevent companies from shopping for favorable auditors, and cooling-off periods when moving, in both directions, between industry and audit roles. Alternative payment models that reduce auditor dependence on auditees should also be urgently explored. Where single auditing organizations lack sufficient expertise, subcontracting and consortia models can enable the necessary breadth across AI evaluation, safety, security, and governance.

Rigor: Processes that are methodologically rigorous, traceable, and adaptive. Audits should follow a standardized process while giving auditors the autonomy to flexibly determine specific methods and adjust scope as issues emerge. Auditors should be able to define evaluation metrics and criteria rather than simply validating companies’ preselected approaches. Wherever feasible, audit procedures should be automated, transparent, and reproducible to support consistent application across engagements and enable continuous monitoring as systems evolve. Auditors need to safeguard evaluation construct and ecological validity, and audit criteria should be protected against gaming. Finally, audits should incorporate procedural fairness, giving companies structured opportunities to correct factual errors while preventing undue influence on conclusions.

Clarity: Clear communication of audit results. Stakeholders must be able to understand the audit results. These should be communicated in audit reports with a standardized structure, covering the audit’s scope, level of assurance, conclusions, reasoning, and recommendations. Results should be communicated appropriately to different stakeholders: to protect sensitive information, auditors and companies can publish summarized or redacted versions for external stakeholders while sharing full, unredacted audit reports with boards, company executives, and, in some cases, regulatory bodies.

Challenges and next steps

Our long-term vision will require concrete efforts by several categories of stakeholders to both achieve and maintain. The most urgent challenges are:

Ensuring high quality standards for frontier AI auditing, so it does not devolve into a checkbox exercise or lag behind changes in the AI industry.

Growing the ecosystem of audit providers at a rapid pace without compromising quality.

Accelerating adoption of frontier AI auditing by clarifying and strengthening incentives.

Achieving technical readiness for high AI Assurance Levels so they can be applied when needed.

These challenges are substantial but not unprecedented. Companies routinely share sensitive information with financial auditors, potential acquirers, penetration testers, and consumer product testing laboratories under carefully controlled terms. We believe similar practices for AI safety and security are both achievable and urgently needed. For each of the challenges we describe, we recommend specific next steps:

Figure 2: Recommendations for next steps across four challenges in frontier AI auditing.

Keeping up with the rapid pace of AI progress and deployment requires quickly importing best practices from more mature industries and immediate investment in auditing pilots, technical research, and policy research. Moving with urgency is essential if frontier AI auditing is to reach maturation and scale alongside AI development.

SHARE ARTICLE: